In response to recent mass shootings, first-person shooter games like Call of Duty have been said to contribute to a “culture of violence” in the US.

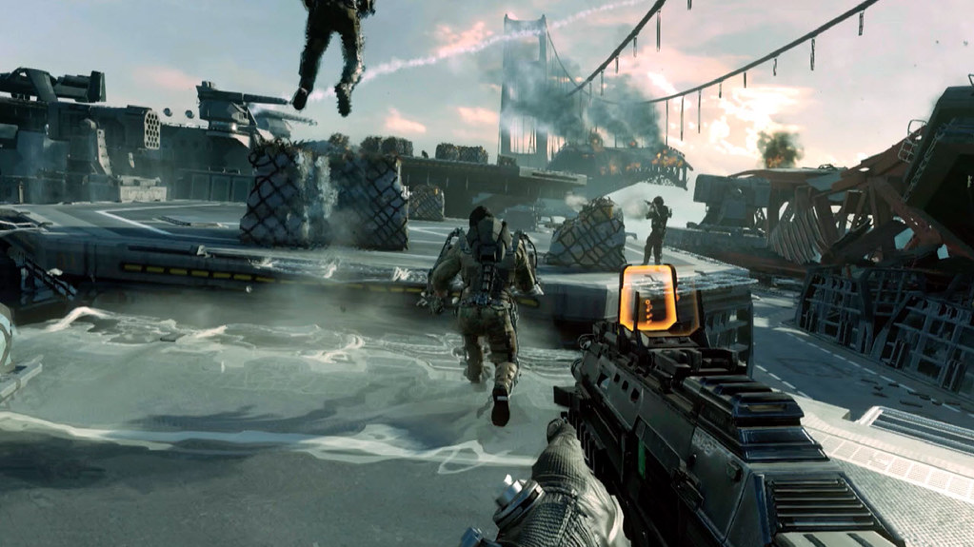

Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare - Multiplayer trailer, YouTube.

August 3 and 4, 2019 were days marred by a familiar tragedy in the United States. In El Paso, TX, and Dayton, OH, 25 lives became victims of mass shootings, with many more being wounded.

As if something like this had happened before, headlines from all sides of the national gun debate (re)surfaced within minutes of the attacks: “The world thinks America’s gun laws are crazy – and they’re right” (The Washington Post); “Gun Owners of America: Guns save lives every day” (USA TODAY); “A new approach to guns in America” (Vox).

However, President Donald Trump, in his official statement regarding the attacks, chose to shift the focus away from guns and the gun debate. In addition to white supremacy and mental illness, Trump called for a curbing of the “gruesome and grisly video games” that contribute to a “culture of violence” in the US. To Trump, a culture where violent video games are easily accessible inherently breeds youth intent on shooting up their local schools, churches, and shopping centres.

National condemnation of violent video games is by no means novel: in the immediate aftermath of the Columbine High School in 1999, parents of victims filed lawsuits against video game manufacturers due to knowledge that the shooters were fans of first-person shooter video games, like Doom. Similar outbursts against the video game industry emerged following the Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, and Orlando shootings.

But as these shootings continue to happen, so too has research investigating the video game/aggression relationship.

In June 2019, Harvard researchers Maya Mathur and Tyler VanderWeele published a meta-analysis of the video game/aggression literature. A meta-analysis can be loosely defined as “research about research”. These types of analyses are valuable as they aim to interpret evidence from individual studies – each with their own findings and limitations — through a holistic perspective in an effort to identify general trends across all the research. In this case, Mathur and VanderWeele looked at studies related to the video game/aggression relationship to determine what the field was finding as a whole.

From their analysis, Mathur and VanderWeele concluded that video games likely do increase aggressive reactions in users, but that the effects are small. That is, violent video games can make people a little more aggressive depending on the circumstances, but not enough to be a significant contributor to extremely violent behavior, like mass shootings.

It should be noted that by opting to shine the spotlight on video games, President Trump did not just choose to ignore data and conclusions presented by researchers like Mathur and VanderWeele; he also chose to ignore the substantial amount of data on America’s controversial gun culture:

- A 2017 survey conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) found that 73% of all homicides in the US were gun-related; to contrast, this value is 38% in Canada and 13% Australia—two countries with much stricter firearms regulations.

- The Small Arms Survey in 2018 found that the US topped the list of countries in terms of firearms per 100 residents at 120.5. The next highest country was Yemen, with 52.8 firearms per 100 residents.

- Of the top five countries in video game revenue, the US has the highest number of violent gun deaths per 100,000 people at about 4.4. The next highest is Canada at about 0.5 per 100,000 people.

Of course, correlations must be made cautiously; guns and the American gun culture may not cause mass shootings. But to argue that violent video games deserve more or even equal blame than firearms would be to discount scientific evidence of the simple truth: they just aren’t.

References:

Mathur, M.B.; VanderWeele, T.J. Finding common ground in meta-analysis “wars” of violent video games. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(4), 705-708.

By: Jacky Deng

Jacky Deng is a graduate student from Surrey, British Columbia currently attending the University of Ottawa. Jacky received an honours degree in Chemistry from the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus (UBCO). During his time at UBCO, Jacky wrote for the university’s student newspaper The Phoenix as its Arts Editor, and eventually oversaw management of the newspaper as its Coordinating Editor. Despite not having pursued a degree or formal career in journalism, Jacky has accumulated a strong science communication portfolio consisting of both journalistic writing and video production. He is passionate about science education, as well as how data can inform decisions related to social issues, environmental issues, and, most importantly, sports. He is currently reading Pablo Escobar: My Father by Juan Pablo Escobar.