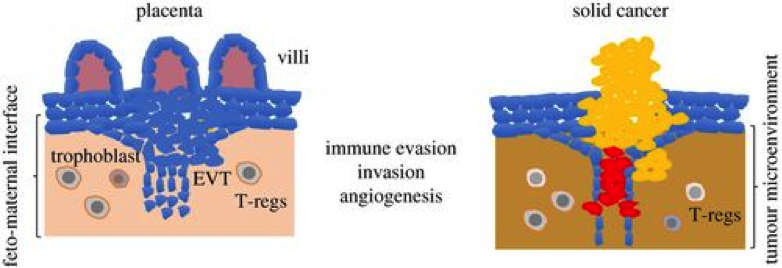

The genetic controls that govern creation of the placenta (left) are similar to those that go awry to touch off cancer. Illustration: Almas Khan, created in BioRender.com

Cancer is a devastating disease marked by defective cells that multiply out of control and go on to invade our bodies. But what if I told you the processes that make cancer so dangerous are normal features of an organ necessary for us in the beginning of our life?

That organ exists for a short time and is usually discarded after we are born. It barely registers in people’s minds beyond that of potentially consuming it for so-called health benefits. Even science has long ignored this multifunctional organ which plays a role in the development of each and every one of us.

That organ is the placenta.

The placenta starts to form when cells from the growing fetus quickly invade and remodel the mother’s surrounding tissue, including reworking blood vessels to aid the growing fetus. This is similar to how a tumour starts to form and triggers blood vessel development to feed its growth.

While the placenta is forming, its cells work hard to inhibit parts of the immune system so the growing fetus isn’t rejected by the body. Various ‘immune evasion’ strategies used by the placenta are also used by cancer cells to prevent growing tumours from being destroyed by killer T-cells. One of these is to recruit regulatory T-cells (T-regs) near the tumour site to suppress killer T-cells that would otherwise destroy the cancer cells.

The placenta has also been found to recruit nearby T-regs to evade the immune system.

The image below shows the similarities between a solid tumour and a placenta at a structural level with blood vessel remodelling and immune modulatory level.

Credits(Constanzo et al. 2017)

Similarities don’t stop at development but occur even at a genetic level. Many tumour suppressor genes (TSGs) which code for important proteins that work to prevent out-of-control cell division in cancer are usually turned off when the placenta is being formed.

Not only that, but chemical markers known as methyl groups, which regulate genes and usually turn them off (but not always), occur in much lower numbers in cancer cells and those that form the placenta. In fact, many studies have found genes expressed in lung cancer, breast cancer, and various other forms of cancer to be similar ‘placenta-specific’ genes.

So, what does this all mean?

Several studies show that cancer rates are higher in placental mammals, that is, those such as cats, cattle, humans and many others that grow a placenta as part of their reproductive process. There is a similarity of genetic control in both in the placenta and in various cancers these mammals get.

An emerging hypothesis states that genes and molecular pathways which allow for placenta formation may somehow become reactivated later in life in cancer.

The placenta provides a rich paradigm to study so-called aberrant processes in a normal context of complex regulation, even with fast growth. It provides some compelling clues as to why things can go so wrong later on.

Resources:

By: Almas Khan

Almas Khan a MSc student in the University of British Columbia’s(UBC) Bioinformatics program. She is studying epigenetic of the placenta and its relation to birth outcomes. She also received her BSc in Microbiology and Immunology at UBC. Outside of the lab, she likes baking, tea, yoga, and reading investigative journalism pieces and fantasy novels